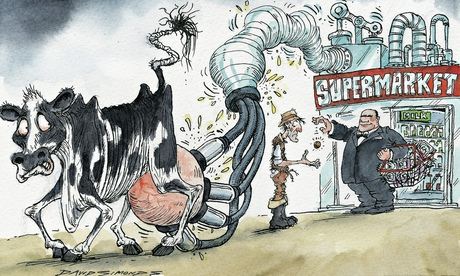

As the row about the price of milk in Britain rages, the most sensible comments have come from the boss of northern supermarket chain Booths.

“We see farmers not just as suppliers, but customers,” Chris Dee, chief executive of Booths, said last week.

The northern base of the family-owned grocer is key, because Booths stores are often located at the centre of rural communities.

“That means farmers have to make a profit, and we recognise that,” Dee added. “Otherwise we would be the bad guys in town.”

Such logic seems to have been absent at Dee’s largest rivals, who have been targeted by farmers angry at the price they are paid for their milk and the amount the supermarkets are importing from outside the UK.

Supermarkets have claimed that the dramatic 25% fall in the farm-gate price of milk in the past year – which is what sparked the new row – is not down to the price war between the grocers.

They have a point. A 50% drop in Chinese imports in the first half of 2015 and Russia’s blocking of western food imports have led to an oversupply of milk in Europe. The farm-gate price of milk in Britain is actually the fifth-highest among the 15 longest EU members. The UK average of 23.66p a litre is also still well ahead of 10 years ago, when it fell to 17p per litre.

However, by backing down in the face of protests, supermarkets have accepted that they are part of the problem facing farmers.

Aldi, Lidl and Asda agreed to pay 28p a litre after their stores and distribution centres were targeted by campaign group Farmers For Action, and Morrisons will pay 26p a litre and launch a new Morrisons Milk For Farmers brand that returns an extra 10p a litre to producers. Tesco also did a U-turn in the face of farmers’ protests and will switch to using British, instead of German, milk in all its own-brand yoghurts.

The newly emboldened campaign groups now want to win further concessions, including a limit on imports of lamb from New Zealand and for Aldi, Lidl, Asda and Morrisons to pay farmers more than the estimated cost of producing milk – which stands at 30p a litre.

To their credit, Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Marks & Spencer and Waitrose have already committed to paying a price for milk that is line with the cost of production. But is this really the pinnacle of what supermarkets can do for their suppliers?

Booths has said it will go further, by guaranteeing to pay the highest price for milk in the British grocery industry. At present it is paying farmers 33p a litre, 10p more than the industry average.

Apart from being a useful PR exercise for Booths, this makes a great deal of business sense. Why would a company not want to ensure that it works with the best suppliers in the industry, and that these suppliers are healthy because it works with them? For a supermarket chain whose suppliers could also become its customers, this question is even more important.

In the motor or aerospace industries, driving a supplier to the wall would be seen as a remarkably short-sighted thing to do. Airbus and Boeing rely heavily on suppliers such as GKN and Rolls-Royce to produce passenger jets.

Yet supermarkets often act like it is a badge of honour to squeeze every last penny out of their suppliers. This is despite the fact that these suppliers are often providing them with a product, such as milk, that will be sold with the retailer’s name on.

Food retailers have already been warned about what happens when they lose control of their supply chain. Only two years ago, Tesco, Asda and others discovered unlabelled horsemeat in their products.

Whatever the reasons behind the dairy farmers’ current predicament – it’s true that many farms need to become more efficient – the episode should remind us that food retailers and their suppliers depend on each other, and greater collaboration is needed between them.

Not just staff losing sleep at Amazon

From what we hear about the bruising and intense working conditions in Amazon’s offices and warehouses, it is tempting to conclude that technology companies are introducing a worrying new culture into the workplace. But not all technology companies are alike. While Amazon offers no paid paternity leave, Google offers 12 weeks and Facebook 17, the best in the US.

(Incidentally Amazon is also run by a chief executive who has gone against the grain in another way – by boasting about how much sleep he gets. “I’m more alert and I think more clearly,” Jeff Bezos has said about a good night’s sleep. “I just feel so much better all day long if I’ve had eight hours.”)

The lesson from the testimonies of Amazon staff is that this is a company pushing its workers to extraordinary lengths in order to be more efficient, but barely even makes a profit.

The complaints about Amazon should alarm investors in the company, who have driven the value of the online retailer to a remarkable $250bn. Not only are the reports damaging to the company’s reputation, but they suggest that Amazon is already going to unprecedented lengths to try to run efficiently.

The dramatic sales growth at Amazon is well known, with revenues still rising by an impressive 20% year-on-year. But its ability to generate profit remains in doubt. In 2014 Amazon racked up a net loss of $214m, despite sales of $89bn. In the most recent quarter, shares in the company rose after it posted a “surprise” profit of $92m. The fact that this profit was made on sales of $23.2bn, shows that Amazon operates with wafer-thin margins.

Bezos has always hit back at critics by insisting that Amazon has a long-term strategy and the profits will come eventually. But with warehouse workers already wearing tags that monitor their efficiency and new mothers criticised on colleague feedback systems for leaving early, it is questionable what more Amazon can hope for from its tireless staff.

Carney off to the mountains for an uphill struggle

Next weekend the Bank of England’s governor, Mark Carney, will attend the annual gathering at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where central bankers meet to mull over the stresses and strains on the global economy after two weeks of turmoil on the world’s stock exchanges.

Until now, Carney has stated that inflation is rising and that it will force the Bank to increase UK interest rates, possibly next spring. But now he must wrestle with a return to falling oil and gas prices, the overproduction of cars and a stalling Chinese economy. All of this will lead to low inflation.

Yet his words will be only barely heard compared to those of Stanley Fischer, the vice-chairman of the US central bank. Fischer is standing in for the Federal Reserve boss, Janet Yellen. He also believes inflation is a worry. Or at least he did. Now there are few figures telling him he needs to signal a rate rise. The likelihood must be that he won’t.