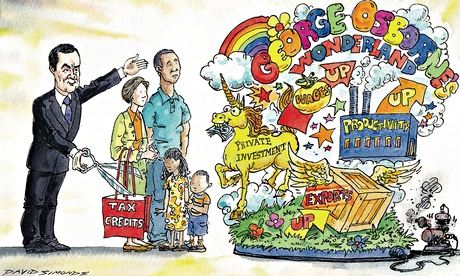

Next year, average wage rises will double to 4% and the economy will be booming. Exports will flourish and private investment will return to pre-crisis levels. Unconfined joy will spread from the south-east northwards, and west to the Cornish constituencies captured by the Tories from the Liberal Democrats.

The optimistic forecasts do not stop there. Unemployment will continue to fall, productivity will rise, and the Bank of England, concerned that the UK’s runaway success is about to generate the return of inflation, will start to put up interest rates at a gentle pace.

It is this rosy view of the future that underpins the Treasury’s drive to cut tax credits in the upcoming upcoming emergency budget. George Osborne appears to believe that his plan to reduce state top-up payments for people in work will soon be forgotten in a booming economy.

Cuts to tax credits could make up £5bn of the £12bn of extra reductions in the welfare bill earmarked by Osborne to help him on his way to a budget surplus in 2019. That’s a hefty whack to households on modest incomes striving to better themselves.

One scenario illustrates the point. Today, a two-parent family with an income of £26,000 who spend £140 a week on childcare for two young children should receive tax credits each year of £2,233. Now let’s say the second earner in this case study doubles their weekly hours from 10 to 20, so earning, say, £7,200 rather than £3,600, and pushing the household income to almost £30,000. Along with that, the government’s tax credit top-up currently more than doubles to £5,052. It’s the reward for working longer hours; and it could disappear in the current review.

Plenty of backbench Tory MPs ask why the state should boost the living standards of families at this income level when they may live in an area where their outgoings are low and their disposable income relatively high. High levels of fraud and errors in calculating tax credits have also discredited the system. Last year, HMRC was reported to be pursuing more than 4.7m cases of overpaid tax credits, amounting to debts of £1.6bn.

But these same backbenchers are wary of moving against a key group of voters ahead of the promised economic miracle. And they should be.

All the data tells us that middle income families are spending only a proportion of their gains from lower petrol prices, cheaper food and a 2% average wage rise. They are clearly nervous, and their reluctance to splash the cash is borne out by the heavy discounting seen on the high street in the summer sales. If these households are told that they can expect to lose a sizeable chunk of their tax credits, their nervousness will only intensify.

The sums under discussion are considerable. Our fictional family begins to lose tax credits once their joint annual income passes the £30,000 mark. Once the joint income exceeds £40,000, it has almost all gone.

The election was won in marginal seats across the east and west Midlands, where families opted for the Tories over Labour in significant numbers. These families are not going to forgive a government that rewards their votes with a financial kick.

Nevertheless, it looks like Osborne is going to take the risk. He knows the plan is a gamble that will fail if employers refuse to raise wages above 2% while inflation creeps upwards. That will only double the pain of tax credit losses, hitting consumer spending and the economy more broadly. Add in the prospect of the Bank of England ratcheting up base rates and hiking their mortgage bill, and families might see the withdrawal of government support as a betrayal.

Now Network Rail has lost its credit, Heathrow won’t be happy

When Network Rail was reclassified as a public body last year, the government and the industry were keen to play down the significance – this was not really renationalisation.

But having the railway’s debt on the Treasury’s balance sheet started to change everything. Before that, the infrastructure owner would not have been too concerned about the mounting costs of work it had promised to carry out; it would simply have borrowed more. Yet now that the railway’s infamous credit card has been snipped up by the Treasury – having run up £38bn and rising of rail debt – promises of jam tomorrow look very hollow.

For Network Rail, and the wider industry, this is grim: the capital it has enjoyed in recent years, financial and political, has been blown. But the ministers who now have to poop the party are the very same as have stoked the festivities in recent years, trumpeting the goodies they were going to deliver.

Even as children’s centres closed and bedrooms were taxed, spending on rail infrastructure somehow was preserved, apparently from a separate, miraculously self-refilling, pot. After this crisis, as the new railways promised to the north and Midlands fail to materialise, rail’s tortuous financing can only come under greater scrutiny.

Rail’s fall from grace, and the demand that it live within its means, could have come at an unfortunate moment for another transport interest. The airports commission is preparing to recommend where to put a new runway this week. While both Heathrow and Gatwick, if chosen, will raise the billions in private money needed to expand, a bigger Heathrow would also need public funds spent on the roads and surrounding infrastructure.

That’s another £6bn, according to the commission – and according to Transport for London estimates, perhaps double that. As the Department for Transport picks over the bones of Network Rail’s five-year plan this summer, it will surely blanch at the idea of demanding billions more for Heathrow.

What don’t bankers understand about being ethical?

Just what has been the point of the $150bn worth of fines that have been slapped on the world’s biggest banks since the onset of the crisis? It a question worth posing after Mark Carney’s remarks on Friday. The governor of the Bank of England said: “A lot of people in these markets didn’t really know – and probably still do not know – what is expected of them because it hasn’t been adequately defined in everyday language.”

It seems unlikely that the hundreds of pages of traders’ chat released by the regulators has not provided a clear example of inappropriate behaviour. Making an example of the offers of champagne and curries to fix interest rates should have been enough of an explanation: after all, the offers themselves could hardly have been expressed in plainer language.

The real problem is that so many bankers appear to have got off scot-free. What is required is more work to ensure that individuals are held accountable for their actions.