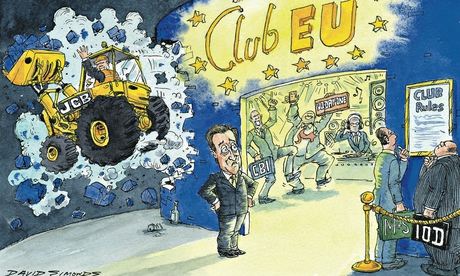

We learned last week that the business world is not united on the burning issue of the UK’s membership of the European Union. There is clearly a powerful pro-EU lobby that will rally to CBI president Sir Mike Rake’s call for business to “turn up the volume” and “be crystal clear that membership is in our national interest”. Vodafone boss Vittorio Colao, for example, said last week: “It’s in the interests of our customers and our shareholders that Britain does not leave the EU.”

But there are also vocal opponents. Graeme MacDonald, chief executive of digger firm JCB, said he did not think a UK exit would make a “blind bit of difference” to trading with Europe. Others advise waiting to see what David Cameron’s attempt at renegotiating the UK’s relationship with the EU yields.

Marc Bolland, chief executive of Marks & Spencer, said: “Some of these reforms can be done and should be done, and it is best for Britain to see what those reforms are before making a judgment.”

That position may also be closer to the mood of the majority of small and medium-sized businesses. In a survey last year the Institute of Directors – which has a very different membership from the CBI, with its battalion of multinationals and large banks – found that for 60% of members, support for continued EU membership was conditional on successful reforms in key areas, such as employment law.

At least we will have a debate. Despite the CBI’s irritating claim to be “the voice of business” (as if there could be only one), Rake is correct on two central points. First, it would be a good thing if business folk spoke “in a language people can understand”. Second, opponents of EU membership should explain in detail what an alternative would look like.

The first point cuts both ways. If employers, when they grumble about the EU working time directive and other employment laws, really mean that they would like greater freedom to fire staff cheaply, they should say so. Such an admission might not convert many waverers to the EU cause, but it would be honest.

Equally, though, directors should feel free to say what Brexit – the UK’s exit from the EU – would mean for jobs and investment at their companies. High-minded notions about open economies and the benefits of free trade don’t cut it. Workers want to know if their jobs are on the line. In the Scottish referendum, the threat of specific jobs and companies moving to England injected a much-needed dose of economic realism into the debate.

Few would mourn the departure of crisis-ridden Deutsche Bank from the City, but if a more respected institution – say, Lloyd’s of London, the insurance market – could make a detailed case about the damaging effect of Brexit on the financial services industry, voters would wish to hear it.

The second point – about an alternative to EU membership – is critical. Here Rake makes a good argument: Norway and Switzerland are not in the EU but still have to abide by EU rules to sell into the single market, so where is the supposed escape from European red tape?

MacDonald at JCB says it is “easier selling to North America than to Europe sometimes”, but why does he believe exit, as opposed to engagement from within, would improve matters?

That’s the challenge to get-out lobby must face. It’s easy to maintain that the UK would be able to negotiate trade deals with countries across the globe, rather than be bound by the EU’s agreements. Of course there could be deals. But would they be better deals? Common sense suggests the US, for example, would give more generous terms to a zone of 500 million citizens than to a single country with 64 million people. If the reality is different, let’s hear a detailed account rather than vague aspiration.

Wonga’s back: would you credit it?

Three years ago Wonga, pumping out profits of £62m on turnover of just £309m, proclaimed its borrowers were “young, single, employed, digitally savvy and can pay us back on time”. Except that much of its lavish profit margin was from multiple fees racked up by less than savvy individuals who did not pay back on time, and who were wiped out by its 5,853% interest rate.

Last month, a humbled Wonga – having been forced to write off loans to 330,000 clients and pay millions after it was found to have issued fake legal letters – reported a loss of £37m. As one wag put it, the loss would only have been £1.50 if it hadn’t taken out a loan with itself in December.

Last week Wonga relaunched, we’re told, to a more middle-class audience. Its less-than-catchy new slogan is “credit for the real world”. Its press release proclaims: “Our focus is on serving hard-working people throughout the UK.” With admirable chutzpah, Andy Haste, the chairman brought in to clean up the operation, said it had decided to keep the Wonga name as it was “still seen as a trusted brand by our core audience”.

That core audience has shrunk dramatically, from more than 1 million to around 600,000 today. Wonga believes new customers will be impressed by a “24-hour money-back guarantee”, a three-day grace period, where customers will escape the £15 default fee, and freezing all balances in arrears to stop them racking up interest for longer than seven days.

It has even slashed the interest it charges. It faces stiff competition, as personal loan rates have tumbled in recent months. M&S Bank is offering an APR of 3.6% (although the minimum term is 12 months, rather more than with Wonga). Nationwide and Sainsbury’s are also charging 3.6%.

So what is Wonga now charging? Its new APR is 1,509%, or, using its preferred calculation, 292%. The Wonga puppets may have been retired but evidently the company reckons there are plenty more muppets out there.

Half a dozen of the other sex isn’t much FTSE 100 progress

A small victory for diversity at the top of Britain’s biggest companies was scored on Friday when Alison Brittain was named as the new chief executive of Whitbread, owner of Premier Inns and Costa Coffee. Not only has Brittain managed to jump sectors – she has spent her entire career as a banker until now – she has managed to take the number of female bosses in the FTSE 100 to six.

Brittain joins Véronique Laury at Kingfisher, Liv Garfield at Severn Trent, Moya Greene at Royal Mail, Alison Cooper at Imperial Tobacco and Carolyn McCall at easyJet in the higher echelons of corporate Britain.

But keep the champagne on ice. In 2015, six female bosses out of 100 should not be a cause for celebration. The truth is that there are still nearly three times as many bosses called John (or Jean) at the helm of big UK businesses as there are women.