Marketing is dead. Strategy is dead. Management is dead.

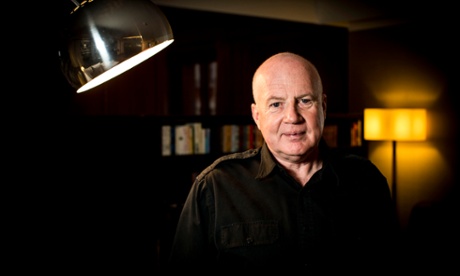

So says Kevin Roberts, the man who ran the UK’s most famous advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi for 17 years, until his recent move upstairs to become executive chairman.

If that seems like a rather pessimistic message for somebody in his relentlessly upbeat trade, then think again. Roberts is just about the most positive man in adland.

Business is now all about creating a “movement” of people with shared values, he enthuses from his suite at London’s luxurious Bulgari hotel, without even a hint of a smirk.

“You do that by figuring out how you add mystery, sensuality and intimacy to a brand ... Sensuality: we feel the world in five senses. Whether you like this room or not, [the architect] Antonio Citterio designed it and all five senses are at work in here. I mean, people want to lick this table.”

When you read back quotes like that, it is tricky to avoid the conclusion that Roberts’ most-trusted soundbites are more David Brent than David Ogilvy, the legendary “father of advertising” who is said to be the inspiration behind Don Draper in Mad Men.

In a similar vein, Roberts nurtures the concept of “lovemarks – the future beyond brands” where he aims to make his client’s brands adored. He paints himself as a “radical optimist” who brushes off cynical questions because: “I don’t provide cynical responses.”

He also publishes his advertising theories in “red papers”, rather than white papers, because “Saatchi & Saatchi operates from the edges ... [it] zigs when others zag.”

Yet somehow, in the flesh, there is something about Roberts’ personality that allows him to get away with all that – well, some of the time.

A quick poll of those who have worked for him generates general praise for his management style. “He really is a good leader,” insists one. “Somehow he makes people feel inspired when he walks in the room. And clients love him.”

“His personality does not transfer to paper,” acknowledges another. “He overdoses on the bullshit massively, but he is a great leader and without him Saatchi & Saatchi would probably not exist.”

Still, the agency - which will forever be associated with the Conservatives’ 1979 election-winning slogan “Labour isn’t working” – now has a new boss in Robert Senior, which begs the question: what is Roberts hanging around to do?

His new role, he says, will allow him to protect the fledgling management team from threats, such as rivals using the transition to poach clients and staff.

“I’d like to be a deterrent in that area that gives [the new team ] just a bit of breathing space, to bring in dynamism, to bring in growth, to bring in innovation, to change stuff without having to worry about their backs,” he says.

“For 2015, I said I’m just going to stay here and make sure those guys have a playing field on which to play.”

“[Senior’s] different to me,” says Roberts. “He’s a classic ad creative, client-focused guy. I’m not particularly advertising or client-focused.”

So what is Roberts, then? “I’m a leader,” he shoots back instantly, before returning to his successor. “And so’s Robert. But he’s a creative and client leader.”

All of which makes Senior sound like an upgrade on his predecessor, but that observation seems to irk Roberts slightly.

He pauses, before deflecting: “David Ogilvy said it is always best to hire people better than you. I think there’s no question [Senior is] a far better adman than me. Will he be a better leader over the next decade? It’s all to play for. God, let’s hope so, eh?

“I love this company. I love Robert. Surely the greatest gift I can give the company is the smartest CEO in the world.”

Certainly that is a worthy aim, albeit one that sounds improbably selfless. Surely human nature means we all secretly enjoy our successors failing a little – or at least them being no better than ourselves?

“When people talk about me, one of the biggest things they say is my generosity,” he says. “And they ask ‘where do you get your biggest pleasure?’ My biggest pleasure is by inspiring people to be the best they can be ... It might sound hokey, but what I’m driven by is trying to make the world a better place through business, because it is the only sort of thing I know.”

In reality, Roberts’ motives appear more personal than that. He lectures widely on business – “I teach serious MBA programmes at Cambridge and at Lancaster and at Auckland,” he says, but his attachment to academia looks to be partly driven by nursing an old sore, rather than pure altruism.

“I got kicked out of [Lancaster Grammar] school [in 1966],” he admits. “I was going out with the deputy head girl at Lancaster Girls Grammar and she became pregnant. It was only the second time we’d done it. I had no idea about male-female reproduction. Her school was fantastic and said: ‘You can stay here and we’ll see you through this.’ My headmaster was a prick from the south ... so the school said to me you can’t stay at school if you’re going to have a child, so you’ve got to get rid of the child. And they took my first XV jersey off me which really pissed me off, because it was the only thing I had.”

He left school that day – immediately married his girlfriend, Barbara, who then had their daughter, Nikki – and took four jobs to support them. He says he was a bricklayer, a barman, a translator in a local import/export business, as well as getting a few pounds during the summer for playing local league cricket.

But that all meant he never went to university, where he had been sure he was heading, an omission that left him lacking academic qualifications which remains a “chip on my shoulder”. Roberts’ website now lists three honorary doctorates and three honorary professorships: “It’s the same chip,” he says.

Yet the honorary awards still look an odd thing to pursue, as his lack of formal qualifications quite clearly ended up being irrelevant. He joined Mary Quant Cosmetics in 1969 as a brand manager, went to Gillette in 1972, then halved his salary to get a break at the consumer products giant Procter & Gamble three years later, before winding up at Pepsi Cola as a regional vice-president of its Middle East division in the early 1980s.

In 1997, he became chief executive of Saatchi & Saatchi which was in financial difficulty and had just ousted founder Maurice Saatchi, and until January had run the business ever since, even though the company was sold to French advertising giant Publicis in 2000.

Yet for all his achievements in adland, his numerous business books and his motivational speaking, even advertising people can wonder if there is more fluff than substance to Roberts: “Did the agency really turn any brands into lovemarks?” asks one.

Meanwhile, this committed Anglican’s belief in “inclusive capitalism” doesn’t quite chime with the case of the 35 unpaid cleaning staff at Saatchi & Saatchi’s Soho office, who have been campaigning to recoup £40,000 of unpaid wages and holiday money from the advertising firm’s contractor, Consolidated Office Cleaning Limited.

“That didn’t even make it to my radar,” Roberts says, while pointing to nappy brand Pampers and former mobile phone group T-Mobile as “lovemarks” that Saatchi helped create.

Still, despite these gripes, Roberts remains defiantly upbeat. And maybe he’s right to be so optimistic – certainly experience suggests that everything seems to turn out rather well for him in the end.

For instance, years after the setback of being kicked out of school, Roberts’ alma mater invited him back to watch the first XV play and for him to address the team. “The captain took off his jersey and gave it to me,” he recalls. “It was the jersey they took away from me. I was pretty moved.”