As any savvy cop knows, following the money is a failsafe way to understand how organised crime works. The same goes for the music business. The industry – by which we mean record companies in the US and the UK – has long been peopled by Svengalis, spivs and gamblers, who are often just a contract on headed paper away from grand larceny.

The trouble with following the money, though, is that the general reader can find the process dry. Artists’ biographies, with their tales of glamour, intoxication and heartbreak are one thing. The biographies of businesses often require a deep commitment to actuarial nuance. Gareth Murphy, author of Cowboys and Indies, has a task on his hands, trying to make the patent wars of the early sound recording era seem sexy. He just about manages it, on what is a whistlestop tour of the entire history of Anglophone record-making.

Like a Mastermind contestant who has unwisely chosen “the second world war” as his subject matter, Murphy takes as his purview the entire shebang, from the birth of recorded sound to the rise of the internet, via the consolidation of the early “indies” – Columbia, A&M et al – into corporate cash cows. In a work only 359 pages long, there are bound to be omissions and jolts as you fast-forward through decades, genres, labels and a dizzying cast of characters. Apple’s iTunes, the arch-disrupter of recent years, only turns up on page 346, having paid the Beatles’ Apple Corps a rumoured $50m to be allowed to deal in music.

This book cannot quite decide whether it is a nerdy tale about sound delivery formats – phonographs and graphophones, 33s and 45s, CDs and iTunes – and their major role in the evolution of the label landscape, or whether it is a story about the egomaniac hustlers behind the music, the Ahmet Ertegüns, the Chris Blackwells, the David Geffens, and their toe-curling antics. It ends up a necessary compromise that leaves you slightly unsatisfied on both fronts. The research is solid: Murphy’s bibliography is pages long, from Fredric Dannen’s pivotal Hit Men (1990) onwards. His original interviews – with Elektra’s Jac Holzman, Def Jam/American impresario and super-producer Rick Rubin, Sire boss Seymour Stein, and Virgin’s Simon Draper among many – are candid and insightful.

Murphy draws a few conclusions. One, that the record industry has nearly imploded numerous times – after the advent of radio, during the great depression, as a result of strikes – and somehow clawed its way back from oblivion. It may yet do so again (although perhaps Murphy is not sure he wants it to, if it means more manufactured pop). He’s on moister ground in his quasi-mystical final chapter, which tries to pin down why anyone in their right mind would run a record label, connecting the ancestral sadness of the Jewish people (significantly represented in the record business) with the ancestral sadness of African-Americans (ditto) as a coda.

Although Murphy’s tracking of his corporate quarry is sure-footed – this is a book in which groovy mavericks repeatedly get swallowed up by the Death Stars of global capitalism – his sympathies lie openly with the record men of the old indies, from Sun’s Sam Phillips onwards.

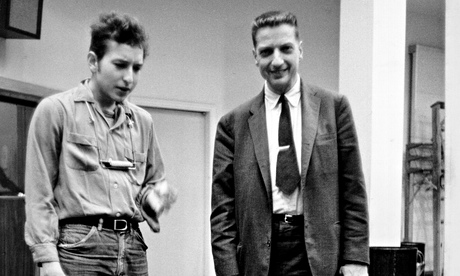

He really loves the aesthete-middlemen who crop up in the right place at the right time to connect talent with funding. The riveting John Hammond, who not only discovered Billie Holiday and Aretha Franklin, but Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen and Bruce Springsteen, deserves his own book (an autobiography is available). A chapter near the end details how Beggars Banquet group boss Martin Mills presides over the contemporary indie landscape like a saviour, with Beggars propping up the entire sector with a distribution network, RTM, and bequeathing the extraordinary success story de nos jours, XL (Adele): again, there’s a fat book in all that.

So for all its sure-footed marshalling of anecdote and figures, Cowboys and Indies sadly isn’t the academic, footnoted doorstop of a tome the subject really deserves . Eccentric giants of the business are reduced to thumbnail sketches to keep the narrative moving along, but no sooner does a fascinating character rear his head – early 70s loft party host David Mancuso, unmotivated by money, is one – than we have to get back to the cloth-eared money men, who are not always bad: Steve Ross, the businessman who bought Warner in 1969, and eventually invented MTV, was a benevolent despot. His purchase of Atari coincided with a prescient worry that video games were hurting music sales, as long ago as the early 1980s. Anyone who has ever boggled at the cut-throat, illogical business of music will glean a great deal from this tantalising overview. The fascinating story of Berry Gordy’s Tamla-Motown has been told umpteen times, but before Murphy, I knew nothing about the business acumen of several generations of Gordys.

Murphy is the author of a series of Buddha Bar compilations, and the son of a music entrepreneur who devised some stadium technology for U2 before the whole thing descended into lawsuits. The recent bonfires of the music industry have cost his friends jobs. History would have answers, he reasoned. One you can comfortably draw is that great music often comes out in spite of, rather than thanks to, the businesses that play midwife to the process.

Cowboys and Indies is published by Serpent’s Tail (£14.99). Click here to buy it for £11.99